Monday, November 14, 2016

Sunday, November 13, 2016

Thursday, November 10, 2016

Wednesday, November 9, 2016

#OromoProtests

Crossing Arms: The Plight and Protest of the Oromo in Ethiopia

by Alexandra Yiannoutsos • • 0 Comments

Equity statement: Accurate information on African politics and culture is extremely difficult to attain. Western countries routinely delegitimize African professionals and news outlets by sharing biased accounts of issues occurring in African countries to African people. I have done my absolute best to adequately research and interview in order to offer the most accurate account of the political situation in Ethiopia and plight of the Oromo people. If you or a loved one is affected by the current situation in Ethiopia or Oromia, and/or you feel that any information is not accurate, please feel free to comment and discuss below.

Following a year of protests carried out by the Oromo people, the Ethiopian government announced a state of emergency in effect for at least six months. The reason cited as violence and unrest among the country’s largest ethnic group. However, the party conducting the offensive is in question. Members of the Oromo community claim that government forces are using excessive brutality to stamp down revolts following what they claim are violations of human and civil rights as well as unjust seizure of private land.

The Oromo community makes up nearly fourty million people, mainly residing within the borders of Ethiopia. The Horn of Africa, a pastoral hub, is continuously marred by its colonial history; one of the main factors creating ethnic, economic, political, and social instability today. Their colonization and fusion into Ethiopian society disrupted the established and independent, political structure of the Oromos while also placing a massive ethnic group in a subordinate position to two other smaller ethnic groups, the Amhara and Tigray.

The current political group in power, The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), is facing scrutiny for its treatment of minority groups. Following the establishment of the 1994 Constitution, after Eretria’s secession and independence, local and international sources began to suspect that the members of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), later reorganizing into the EPRDF, manipulated the country’s constitution for its own aims:

“The TPLF-dominated EPRDF intentionally included Article 39 [The right to secession] in Ethiopia’s 1994 Constitution so that the Tigray region could loot Ethiopia of its resources, use the Ethiopian military to expand the borders of Tigray, and then secede from Ethiopia”.

“The TPLF-dominated EPRDF intentionally included Article 39 [The right to secession] in Ethiopia’s 1994 Constitution so that the Tigray region could loot Ethiopia of its resources, use the Ethiopian military to expand the borders of Tigray, and then secede from Ethiopia”.

Under the false impression that the TPLF/EPRDF are adequately democratic entities, the global community continues to uphold support and offer aid to the government. In the 2015 general elections, the ERPDF won one hundred percent of parliamentary seats. in the previous election the party won 99.6%. Election results like this one reveal that the government is, in all reality, authoritarian, masking their lack of democratic principles with elections as well as the elimination of rivaling civil society groups and independent media. Peaceful, anti-government protests erupted across the Amhara and Oromia regions following the election results. Between November 2015 and August 2016, at least 500 protesters were killed by security forces and thousands detained under terrorism charges.

10,000 people march for Oromo demonstration in Seattle Washington. Credits: https://biturl.io/VRsTq4

Successive government leaders have been cited by Human Rights Watch and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) for human rights abuses as well as non-democratic and severe “iron-fistedness” against dissension; such as, “the Charities and Societies Proclamation of 2008. This restricts Ethiopian non-governmental organizations from embarking on any human rights-related work if they receive their funding from foreign source” according to Adeyinka Makinde of Global Research. The EPRDF has the capacity to stamp down any and all forms of dissension due to its “full control of the security apparatus, the military, the police force and the intelligence services, dominated by ethnic Tigrayans”. EPRDF also legitimizes the use of extreme force under its “vaguely drafted counter-terrorism laws”.

Why Now?

The most recent protests and government crackdown have entered international focus with figures such as Olympic silver-medalist Feyisa Lilesa crossing his arms in solidarity with the Oromo people during the Rio 2016 Olympics.

Feyisa Lilesa crosses his arms in solidarity with the Oromo people when finishing 2nd in the 2016 Rio Olympics Marathon Race. Credits: https://flic.kr/p/LgPMgh

The Oromo people endured oppression for the past century; the question remains as to why, finally, the Oromo peoples’ protests have gained traction.

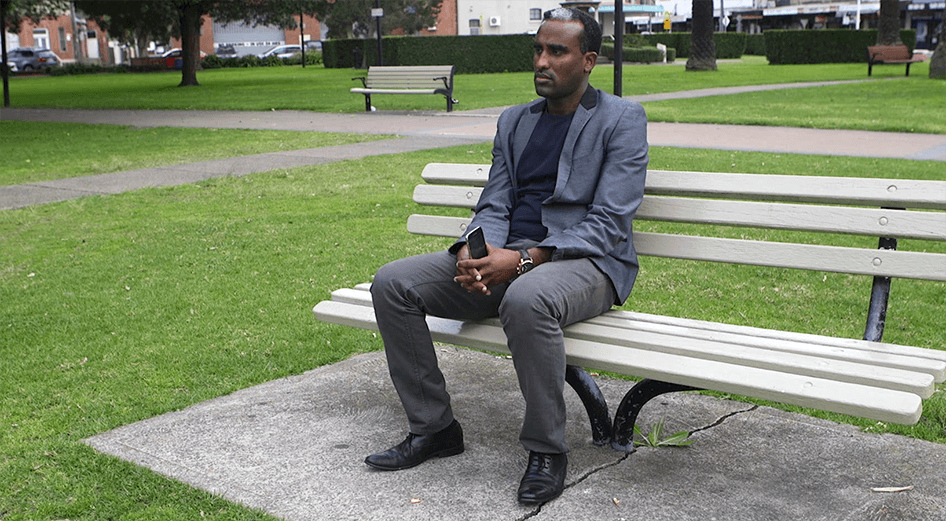

In an interview with Gemechu Mekonnen, an undergraduate student studying at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, an Ethiopian, and an Oromo, he explained that the oppression of the Oromo people reached a tipping point around a year ago when the government planned to enact what is coined “The Master Plan” to seize Oromia land. Farmers around the capital would in turn, lose their source of income with little to no compensation while the government sold their property, arguably for some the most fertile land in Africa, to foreign investors such as China.

Man holds sign in protest of Ethiopian government Master Plan to seize Oromo property. Credits: http://bit.ly/2fqlO5B

The lack of representation, subjugation and oppression of the Oromo group by ethnic groups such as the Ahmara and Tigray resulted in an “unsurprising amount of frustration and resentment”. the Ethiopian government had, “already taken the dignity, voice, and lives of so many, [that] the Oromo people finally said ‘enough is enough’ to the government’s unjust actions”.

Understanding a country’s history and human rights record, while necessary, is not sufficient to comprehend the opinions, needs, and future of an ethnic group. Mekonnen’s insight offers a rare and intimate perspective on the plight of the Oromo people, their tenacity, and their unwavering battle for self-determination:

“The ‘why now’ really comes rooted in many different now. Whether it’s the influence of globalization revealing more of the world to Ethiopians [and to] Oromos, the emboldened and educated students and youth [who] question the status quo, or the blatant lack of respect for the land and life of their people, all these [factors] were important in catalyzing the active voices for change that now exist. The more the government tries to arrest journalist, suppress independent media, and kill opposition leaders, the more the people protest”.

“The ‘why now’ really comes rooted in many different now. Whether it’s the influence of globalization revealing more of the world to Ethiopians [and to] Oromos, the emboldened and educated students and youth [who] question the status quo, or the blatant lack of respect for the land and life of their people, all these [factors] were important in catalyzing the active voices for change that now exist. The more the government tries to arrest journalist, suppress independent media, and kill opposition leaders, the more the people protest”.

The more pressure the international and domestic community puts on the government, the greater the voice the Oromo people have to advocate or their rights domestically and on a global stage. However, signs of progress are small and incremental. On October 2nd 2016, an estimated 678 civilians were killed and countless injured by government forces in what is now infamously known as The Irreecha Massacre. Nearly two million people from across Oromia assembled to celebrate Irreecha, a festival marking the changing of seasons. Irreecha, for many Oromo, is a setting for “resistance and reaffirmation of identity” where attendees sing revolutionary songs and denounce human rights abuses. Following what the attendees considered a politicization of the festival, an individual openly defied the organizers (who were affiliated with the government) and spoke out against the EPRDF. Security forces responded by firing bullets and tear gas on the unarmed participants. Repeatedly hearing news about the tragic loss of life of his people leaves Mekonnen feeling “a sense of hopelessness”. He describes “a recurring feeling dread, not for what could happen to me, but for what is most likely happening to the family I have in Ethiopia”.

The situation in Ethiopia reaches far beyond its borders. The Oromo peoples’ struggle, while inadequately understood by the rest of the world, is catalyzing what will be true, grass-roots changes. There remains much reform that needs to be done regarding Oromo self-determination and within the Ethiopian government itself, but the process has begun. It is important for the international community to recognize the atrocities occurring within Ethiopia as well as stand in solidarity with the Oromo people and the victims of violence and human rights abuses.

Tuesday, November 8, 2016

#OromoProtests

Australia: Protests Prompt Ethiopia Reprisals

Visa for Abusive Ethiopian Official Raises Concerns

(Sydney) – The Ethiopian government has arrested and detained dozens of relatives of Ethiopians who participated in a Melbourne protest in June, 2016, and is still holding many of them four months later, Human Rights Watch said today.

Ethiopian Australians protest against an Ethiopian government delegation visiting Melbourne, Australia, June 2016.

© 2016 Private

On June 12, members of Australia’s Ethiopian community who are from Somali Regional State protested the visit to Australia of an Ethiopian regional government delegation that included Abdi Mohamoud Omar, known as Abdi Iley, the president of Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State. They were also protesting Australia’s support for the Ethiopian government. The Ethiopian delegation did not appear, and after several hours the event was cancelled. The protesters later learned that several dozen of their relatives in Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State had been arrested and detained due to their involvement in the Melbourne protest.

“Abdi Mohamoud Omar and his colleagues have added collective punishment to their long list of abuses against the people of Somali Regional State,” said Felix Horne, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The Australian government should raise their concerns with their Ethiopian counterparts at the highest levels.”

Ethiopian Somali protesters in Melboune expressed particular concern over Abdi Mohamoud Omar’s visit. The Liyu police, a paramilitary unit that reports directly to Abdi Mohamoud Omar, has been responsible for numerous serious human rights abuses, including extrajudicial executions and torture. Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade told Human Rights Watch that Abdi Mohamoud Omar’s visa application did not raise any serious concerns. The Australian government should ensure that foreign officials implicated in serious human rights abuses do not receive visas, Human Rights Watch said.

Numerous Ethiopian Somali Australians said that pro-government supporters living in Australia regularly harass community members perceived as government opponents. Several protesters said that these supporters called or personally confronted them in the days following the arrests and pressed them to make a video pledging support for Abdi Mohamoud Omar in order to secure the release of their relatives. At least three members of Australia’s Ethiopian Somali community have done this.

One man described pleas from his family members: “If you do not record something, they will kill us.”

Threatening demands for video apologies have been a regular tactic of the Somali Regional State government, Human Rights Watch said. People from Somali Regional State who live in the United States, Canada, and northern Europe have described similar networks and tactics by pro-government supporters there. These videos are often posted to the state-run broadcaster, ESTV, and to various pro-government websites.

Shukri, a Somali-Ethiopian Australian, who protested against the visit of Ethiopia’s President of the Somali Regional State, Abdi Mohamoud Omar, to Melbourne, Australia, in June 2016. In retaliation, Ethiopian paramilitary police rounded up members of Shukri’s family in Ethiopia.

© 2016 Human Rights Watch

“I don’t feel safe here,” one Australian said. “I thought I was safe. When I came, [I thought] now I will be in a free country. To be in Australia and be scared all the time, it doesn’t go together.”

One of the recently released detainees told his relative in Australia that security personnel hit him every night. His interrogators told him: “If you want to be released, you have to talk to [your relative] about support[ing] the government. You have to talk to people and then those people will take it to the embassy.” Arbitrary detention is commonplace in Somali Regional State, and detainees describe frequent torture and other ill-treatment in the region’s many detention sites.

Australia has a strong and growing economic relationship with Ethiopia, and Australian companies are exploring opportunities in Ethiopia in mining, energy, and agriculture. In July, an Australia trade delegation from the state of Victoria visited Ethiopia.

Granting a visa to Abdi Mohamoud Omar, who previously visited Australia in 2012, raises concerns about the Australian government’s vetting process of people implicated in serious rights abuses. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection is responsible for assessing visa applications and can refuse visas to people suspected of involvement in war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. Given the significant evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity by Ethiopian forces in the country in 2007-2008 while Abdi Mohamoud Omar was the Somali Regional State head of security, his visa application should have raised serious questions, Human Rights Watch said. However, Australian government officials told Human Rights Watch that Abdi Mohamoud Omar’s visa raised no red flags.

In response to a letter from Human Rights Watch, the Australian government wrote that “all non-citizens wishing to enter Australia are assessed against relevant public interest criteria, including foreign policy interest, national security and character requirements in accordance with relevant legislation. This includes foreign officials with potential character concerns or subject to allegations of human rights abuses.”

A Somali-Ethiopian Australian who protested against the visit of Ethiopia’s President of the Somali Regional State, Abdi Mohamoud Omar, to Melbourne, Australia, in June 2016. “My mother, brother, and sister were all arrested back home. It makes me sad. I was driving a taxi, but I cannot work now. I can’t answer the phone. I cannot sleep. All my family. It’s because of me.”

© 2016 Human Rights Watch

“Ethiopia has severely cracked down down on protests at home, but has gone a cruel step further by trying to silence Ethiopians protesting abroad by punishing their family members,” Horne said. “These relatives are being wrongfully held and should immediately be released.”

For additional information, please see below.

The Melbourne Protest

The generally peaceful protest on June 12 was marred by several scuffles, in which one man was injured, and the filming of protesters by government supporters. Several protesters said that a United States citizen connected to the Ethiopian ruling party, who was traveling with Abdi Mohamoud Omar, threatened protesters, saying “You will see what will happen to your relatives.” Another protester said that pro-government Ethiopian Australians threatened him at the event, saying, “You will see what happens.”

Several witnesses said that Ethiopian government supporters filmed them using smartphones, which would facilitate identifying their relatives in Somali Regional State. Within hours, protesters started receiving calls from family members in Ethiopia saying that relatives – some as old as 85 – had been arrested because of the Melbourne protest.

One protester said he later heard from his family: “When they [Liyu police] arrested my brothers, they told them, ‘Your brother is protesting and that’s why we are arresting you.’”

Another protester said, “Around 8 p.m. I got a phone call from my uncle back home. He said, ‘Two of your uncles were taken by the security and we don’t know where they went. … [I]t’s about you as they said your nephew did this or that to President Abdi Iley [Abdi Mohamoud Omar], that’s why.’ They took them away to jail.”

The 70-year-old mother of a protester was among those arrested. Before taking her to a military camp, the Liyu police asked her: “Are you the mother of [name withheld]? Your son created trouble for the [regional] president.” She was held for almost a month. She told her son that uniformed captors had beaten her in custody.

Ethiopian government delegation, led by Abdi Mohamoud Omar (center), meets with Australian government officials in Canberra, June 2016

Some other relatives of protesters, particularly the sick and the elderly, have also been released, but on the condition that their Australian relatives make a video apologizing to Abdi Mohamoud Omar for their “anti-government” behavior. Other relatives arrested following the protest remain in detention in various locations in Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State.

Conflict, Abuses in Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State

Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State, consisting largely of ethnic Somalis, has been the site of a low-level insurgency by the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) for more than 15 years. The ethnic Somali armed movement, largely supported by members of the Ogaden clan, has sought greater political autonomy for the region. Following the insurgent group’s April 2007 attack on an oil installation in Obole, which resulted in the deaths of 70 civilians and the capture of several Chinese oil workers, the Ethiopian government carried out a major counterinsurgency campaign incurring serious human rights abuses.

In 2008, Human Rights Watch found that security forces were involved in extrajudicial executions, torture, rape, and forced displacement of civilians. Human Rights Watch believes the Ethiopian National Defense Force and the insurgent group both committed war crimes between mid-2007 and early 2008, and that the military could be responsible for crimes against humanity. Abdi Mohamoud Omar was the head of security of Somali Regional State during this period.

Since 2008, the paramilitary Liyu police, who report directly to Abdi Mohamoud Omar, have frequently been accused of extrajudicial killings, torture, rape, and violence against civilians accused of supporting or being sympathetic to the ONLF, including in 2012 when the Liyu police summarily executed 10 civilans. Abdi Mohamoud Omar has been the president of Somali Regional State since 2010. Since 2008, a number of victims of government abuses have told Human Rights Watch that Abdi Mohamoud Omar was present during interrogations, ordering – and in some cases directly involved in – their torture and that he was present during executions of civilians.

One man detained in 2006 in a military camp told Human Rights Watch in July 2016:

When Abdi Iley [Abdi Mohamoud Omar] got frustrated that they [soldiers] did not do what he wanted then he did it himself. He would tell them to hit harder or take matters into his own hands. Abdi Iley [Abdi Mohamoud Omar] would say “You must confess.”

I was tortured. … We were handcuffed with our arms over our legs, with the legs pulled up. They would put a rod under our legs and hang us up so our head falls back and we hang upside down. I would be hung upside down for periods of 15 minutes and they would hit my buttocks and feet. It was very painful. They would keep us like this for 15 or 20 minutes.

Abdi Iley [Abdi Mohamoud Omar] was present for some of these interrogations when we were hanging upside down. The stick was like a rubber hose with an iron bar inside. Once, Abdi Iley[Abdi Mohamoud Omar] thought the officer was not hitting hard enough [so] he took an iron bar himself.

A number of people have also alleged that Abdi Mohamoud Omar threatened them on social media. Limitations on access to Ethiopia in general, and Somali Regional State specifically, have not made it possible to corroborate these claims.

The Ethiopian government has never meaningfully investigated abuses by the military or Liyu police in the Somali region. International human rights groups are not permitted access to to the area.

The government has used various tactics to silence the diaspora. Human Rights Watch has documented numerous examples in which family members of Ethiopians who have been vocal abroad were targeted for arrest or harassment. They have also been targeted for surveillance using European-made malware. Diaspora-based websites are often blocked inside Ethiopia, and the government regularly jams diaspora television and radio stations.

#OromoProtests

Rights group, Ethiopian community say relatives jailed after Melbourne protest

November 7, 2016 in Human Rights, Oromia

Protesters in Ethiopia damaged almost a dozen mostly foreign-owned factories and flower farms and destroyed scores of vehicles this week, adding economic casualties to a rising death toll in a wave of unrest over land grabs and rights.

(SBS) — A new push is being made to secure the release of relatives of up to 30 Australian Ethiopians allegedly being detained in Ethiopia.

As many as 30 relatives of African-Australians have allegedly been detained in Ethiopia following a Melbourne protest in June.

There are calls for the Australian government to help negotiate their release.

In June, sections of Melbourne’s Oromo community protested against a visit by a key member of Ethiopia’s ruling party, Abdi Mohamoud Omar.

The international human rights organisation Human Rights Watch alleges he had committed human rights abuses.

“Family friends would call us and say, ‘Your family got locked up. Why you guys protest?'”

But pro-government supporters photographed the rally, and protesters, who requested anonymity, say the consequences were swiftly felt in their homeland.

“I found out the next day all our family were arrested. Family friends would call us and say, ‘Your family got locked up. Why you guys protest?'”

Human Rights Watch’s Elaine Pearson says, initially, there were reports of 30 arrests of relatives from the Melbourne protest.

She says some have subsequently been released, but others remain unaccounted for.

“We’re concerned that, now, it’s four months later, and, still, some of those relatives remain in detention and pretty much incommunicado.”

Sinke Wesho, from Melbourne’s Oromo community, says jailings emanating from the Melbourne rally could deter many from advocating on behalf of loved ones in need.

“My family, most (of) the men are in prison back home. I feel responsible that I need to respond to their cries, but I can’t do much.”

The head of Melbourne’s independent African Think Tank, Dr Berhan Ahmed, says the Ethiopian leadership in Australia should take a stand.

“To say, ‘Yes, this is a crisis that we need to deal with, and we are putting together a strategy to deal with it. And every person has a right to protest and address issues of their concern.”

A spokesman for the Ethiopian government has flatly denied the allegations.

He has told SBS: “Nobody has been detained in Ethiopia because of his or her relative’s participation in Australia, and the person who gave you such information was trying to mislead you.”

Human Rights Watch has questioned how Abdi Mohamoud Omar was ever issued a visa to visit Australia.

The Federal Government says all non-citizens wishing to enter Australia are assessed against relevant public-interest criteria, including foreign-policy and national-security interests.

It says that includes what it calls foreign officials with potential character concerns or subject to allegations of human rights abuses.

Human Rights Watch is urging the Australian government to negotiate the immediate release of anybody detained as a result of the Melbourne rally.

#OromoProtests

Irreechaa Massacare in

Oromia Oct.2 2016

The holiday

of Irreechaa is a well-respected holiday among the Oromo people. Therefore,

people come every year to celebrate this holiday from every corner. Likewise,

around 2 million oromos gathered in Bishoftu on October 2.2016 to attend this

celebration. However, the enemy of the people had deployed its army with a

mission to destroy the happiness of the Oromo people by massacring innocents

who were only gathered for the celebration.

The people

began to peacefully protest to express their discontent to the system. The

protest was triggered by the unwelcomed activity of the government people on

the stage, as the Oromo people have already had an anguish as a result of a long

time suffering and torture.

The regime

which already had the plan of killing started shooting to the people which

transformed the day to a sad Irreechaa day, which the history of Oromo will never

forget. Though, the official report of the government undermines the count only

to 52 dead, the real figure was around 500 as of many reliable sources. The

incident had even got a wide media coverage around the world.

History will

remember this day as dark, bitter and disastrous day for the entire Oromo

people. We will never forget the martyrs of that day and we will avenge the

death of all freedom fighters of Oromia who sacrificed their lives to the cause

of freeing their people.

The enemy

never stops killing our people for a day, even on this unique day of Irreechaa.

Therefore, I urge all Oromos living inside the country and abroad, as it is our

duty, to come together and to overthrow Woyane (the current regime) just as

they threw our people in to the ditch.

A soldier

may fall, but the struggle continues

Victory to

the Oromo people!

Writen by

Tofik

Abdullah Jamal

Monday, November 7, 2016

Sunday, November 6, 2016

Saturday, November 5, 2016

#OromoRevolution

One Of The World’s Best Long Distance Runners Is Now Running For His Life

As marathon runner Feyisa Lilesa crossed the finish line to win the silver medal at the Olympics this summer, he raised his arms over his head in an X to defiantly protest the Ethiopian government’s treatment of his fellow Oromo people. Three months later, unable to go home or see his family, he contemplates the price of being a world-class athlete speaking out.

Hannah Giorgis

BuzzFeed Culture Writer

As 26-year-old Ethiopian Olympic marathoner Feyisa Lilesa neared the finish line at the 2016 Rio Olympics with what would be a blazing time of 2:09:54, fast enough to win a silver medal in the men’s marathon, he felt no sudden wave of euphoria.

Instead, Lilesa took a deep breath and carried out the plan he’d dreamed about from the moment he was selected to compete in Rio: He crossed his arms above his head in an X. Putting them down for a quick moment and raising them again, he held the gesture as he ran through the finish line with his country’s strife running through his head.

“I knew by all accounts I was supposed to feel happiness in that moment, but all I could think about was the people dying back home,” the long-distance runner told me in Amharic when we spoke in Washington, DC, in September.

Lilesa’s gesture was unfamiliar to most international viewers, but Ethiopian audiences around the world recognized it immediately as the sign associated with anti-government protests stemming from Lilesa’s home region of Oromia, which have been growing in breadth and intensity since November 2015. The #OromoProtests contend that the country’s current government represses its largest ethnic population both culturally and economically.

Later, after flowers were placed around his neck at the end of the race, Lilesa prepared to make a second statement — this time at the post-race press conference. Stepping up to the conference-area podium with his official jacket unzipped — to disrupt the block text bearing Ethiopia’s name — he raised his arms once again and crossed his wrists above his head, spotlighting a wristband in Oromo colors: black, white, and red. If the first gesture could have been interpreted as spontaneous, Lilesa used this second one to make evident his long-held plan to speak out.

Feyisa Lilesa crosses the finish line to win silver during the men’s marathon. Matthias Hangst / Getty Images

Despite government spokesman Getachew Reda’s insistence that Lilesa would receive a “hero’s welcome” if he returned to Ethiopia, Lilesa told reporters in Rio he knew he could not go home without either being either jailed or killed for his actions. In fact, subsequent airings of the Olympics in Ethiopia did not show his gesture, and few state-run print publications covered that or even his win — at all.

Lilesa told journalists he’d seen the government’s duplicity with his own eyes: “The state-run Oromia TV posted on Facebook after I won saying, ‘Feyisa Lilesa successfully sent the terrorists’ message to the international community,’ but they immediately took down that message and changed their narrative” to a more positive one echoing spokesman Reda’s statement.

Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter forbids explicit political activity, decreeing that “No kind of demonstration or political, religious, or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues, or other areas.” But sports — and the Olympics in particular — have long played host to protests both quiet and overt, a stage for the world’s greatest to express both physical rigor and patriotic dissent.

In 1968, American gold and bronze medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos were sent home from the Summer Olympics in Mexico City and suspended from the US team for raising a fist in the air as they stood on the podium during the national anthem. In the aftermath of the protest, they lost their medals, their reputations, their friends, and in Carlos’s case, a marriage. Lilesa had never heard of John Carlos and Tommie Smith before he protested, and Colin Kaepernick’s national anthem protest had not yet garnered headlines. Becoming a hero or entering historical record was never part of Lilesa’s plan.

But online, Ethiopians around the world were discussing his historic show of solidarity. All over Facebook, Viber, and WhatsApp, Oromo people were changing their avatars to pictures of Lilesa with hands raised and wrists crossed in front of him. At the end of his race, he’d emerged a hero to Oromos everywhere, even with his own future uncertain.

Days later, Lilesa saw rumors on social media that his friend Kebede Fayissa was among the countless dead after a fire — and officers’ bullets — erupted at a prison just outside Addis Ababa. He called home from his Rio hotel; confirmation of the news strengthened his resolve to continue speaking out.

American athletes Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos (right), protest with the Black Power salute at the Summer Olympic Games, Mexico City, October 1968. John Dominis / Getty Images

For Lilesa, the choice to protest came at tremendous personal cost. His wife and two young children, whom he did not inform of his plan to protest, live in the nation’s capital. He kept the decision from them, afraid they might compel him to change his mind. As an athlete, he supported them and his extended family, living a fairly comfortable life compared with those around him: He had his own house, a car, and an athletic career that had been thriving since he’d won the Dublin Marathon at only 19. Athletes are among the most respected public figures in the country, and remaining publicly apolitical — or even performing gratitude to the Ethiopian Athletics Federation — would have eased Lilesa into a simpler life. But amid the chaos that ensued after his protest, Lilesa lost valuable training time; his diet changed in transit, and the stress of impending exile wore on him.

The resultant series of setbacks will keep him from competing in this year’s New York City Marathon. Afraid to return home amid worsening political unrest, Lilesa is now training in Arizona for April’s London Marathon. Nine thousand miles away from his wife, his children, and the community he holds closest, he contemplates the personal cost of his protest.

To stay silent with the world’s eyes trained on him would have been a wasted opportunity to attract the media and political attention Lilesa believes is necessary to bring about change in Ethiopia. Progress in the region has not been linear, but Lilesa’s actions marked a catalyst: In the months since his protest, Western media coverage of the country’s political affairs has both increased and taken on a more widespread critical lens. “The little happiness I feel now is because I was able to show the world our desire for peace and it’s reached the world’s media,” he said.

But Lilesa himself lives in fear despite being one of the world’s most celebrated and talented elite athletes, the course of his life and career effectively derailed by the decision to speak out. At the apex of his career, one of the best runners in the world is now running for his life.

Feyisa Lilesa, photographed on September 13, 2016. T.J. Kirkpatrick for BuzzFeed News

The Oromo account for almost 40% of Ethiopia’s population — an estimated 39 million people — and a disproportionate amount of the nation’s elite runners. Born in 1990, Feyisa Lilesa grew up in Jaldu, a district in the West Shewa region of Oromia. The child of farmers, he was the second of seven children raised in a farming community about 75 miles west of Addis Ababa. Like many children in the surrounding area, Lilesa grew up thinking of running as a way to get to his classes — or as fellow runner Biruk Regassa told me, “When school is far, everyone is a runner.”

Since November 2015, protests in the region have sprung up in response to what the government called its “Addis Ababa Integrated Regional Development Plan,” or “Master Plan.” The plan outlined the method by which the federal government would integrate the capital city, Addis Ababa, with surrounding towns in Oromia.

Concerns over the proposed expansion were raised in 2014 by farmers who feared the government’s ongoing takeover of their land would expand under the plan. Uniting under the hashtag #OromoProtests, citizens of the region organized to make their concerns known: The re-zoning plan would constitute an effective government takeover of their land, yet another blow to their autonomy and livelihood after years of ongoing repression.

In January, however, the Ethiopian government announced it would abandon the Master Plan following the deaths of an estimated 140 protesters in clashes with federal security forces. The televised government statement, which has since been removed from the state media where it was originally aired, cited a “lack of transparency” and “huge respect” for the Oromo people as reasons for the decision to scrap the widely opposed plan. But activists — and Lilesa himself — contend the plan was just one flash point in Oromos’ ongoing struggle for equal rights.

The presiding political coalition, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), rose to power in May 1991. Before the May 2015 elections, the EPRDF, led by Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, held all but one seat in the nation’s 546-seat parliament. Amid widespread claims of intimidation and suppression of media, the coalition secured a landslide victory, claiming every single seat. Many opposition leaders contend that the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front party, which represents Ethiopia’s Tigrayan minority (approximately 6% of the population), holds all the power within the ruling EPRDF coalition — and by extension, within the country. The Oromo People’s Democratic Organization, another one of the EPRDF coalition’s four parties, is viewed by many as a comparatively toothless group.

The Oromos have found an unlikely ally in the Amhara, the nation’s second-largest ethnic group. The Amhara comprise about 26% of the population; together, the groups account for about 65% of Ethiopia’s estimated 100 million people. After over a century of oscillating tensions, the two ethnic groups are coming together to protest what they say is shared repression under a Tigrayan-led government and the #AmharaProtests movementhas been rapidly gaining steam. Many people, Lilesa included, note that the groups’ unprecedented union against the EPRDF could portend “Rwanda-like” ethnic conflict in the country.

Lilesa said he has been bearing witness to ongoing discontent in Oromia since well before this round of protests. Born just a year before the EPRDF came into power, he grew up seeing the repression of his people — so helping protesters came as second nature to him.

“People are being exiled from the place I was born, so I tried to do what little I can to help; sometimes I give them my shoes or a little money,” he said. “But after I started doing that, people told me the government had become suspicious of me. Because I trained in the countryside, I feared they could come at any moment and just snatch me.”

“People are being exiled from the place I was born, so I tried to do what little I can to help; sometimes I give them my shoes or a little money,” he said. “But after I started doing that, people told me the government had become suspicious of me. Because I trained in the countryside, I feared they could come at any moment and just snatch me.”

Lilesa during the men’s marathon post-race press conference. Lucy Nicholson / Reuters

It’s part of what made him take his protest to the Olympic stage, pushed by a growing sense that only international intervention would change the situation in Ethiopia for the better. Protesters and opposition forces had been agitating for so long and facing only violence in return because their pleas were not heard by international press, he insisted.

“I would have regretted it for the rest of my life if I didn’t make that gesture,” he said. “I knew that the media would be watching, and the world will finally see and hear the cry of my people.”

“We just want peace, we just want equality,” Lilesa said. “That’s why people are still protesting. Even if [the government] says there is no Master Plan anymore, they are still killing us.”

Human rights organizations estimate state forces have killed over 500 protesters in the last year, with elections taking place against a backdrop of “restrictions on civil society, the media and the political opposition, including excessive use of force against peaceful demonstrators, the disruption of opposition campaigns, and the harassment of election observers from the opposition.”

From the minute Lilesa crossed his wrists as he crossed the finish line in Rio, things moved quickly. He says the moments immediately following his gesture still feel like a blur of cameras and rapid-fire questions from journalists, but he remembers his fellow Ethiopian athletes’ embrace as he left the Olympic Village vividly.

“The athletes cried. They sent me off with tears,” he said. “I’m usually not the kind of person that cries, but they actually made me cry, saying goodbye.”

“The federation officials knew that they would get in trouble if they spoke with me or if they helped me,” he continued. “They gave me some signs and gestures but that was really it because they could not really do much because they presumably had concerns for their safety.”

“The federation officials knew that they would get in trouble if they spoke with me or if they helped me,” he continued. “They gave me some signs and gestures but that was really it because they could not really do much because they presumably had concerns for their safety.”

T-shirts made for Lilesa’s welcoming ceremonyHannah Giorgis / BuzzFeed News

Within hours of his protest, a GoFundMe page to support Lilesa and his family was launched and exceeded both its initial $10,000 goal and the subsequent $40,000 goal. It has since raised a total of over $160,000, much of which has been set aside for Lilesa’s legal expenses. Oromo friends like Bayissa Gemechu, a sports agent who had just left Rio after his wife Tigist Tufa competed in the women’s marathon a week earlier, raced back to his side. By the time Gemechu arrived back in Rio to meet Lilesa, the US embassy had already heard of his case — and made the decision to allow him to apply for a special skills visa into the country from Rio instead of insisting he return to Ethiopia to do so.

Bonnie Holcomb, an American anthropologist who has been closely involved with the Oromo community since living in Oromia during the last years of Emperor Haile Selassie’s reign in the early ’70s, also played an integral role in supporting Lilesa from the US and facilitating his contact with Brazilians who would ensure his safety. Holcomb, the co-author of a book investigating Ethiopia’s political history, reached out to Brazilian friends who helped shepherd Lilesa’s visa application process.

The Brazilian couple contacted their local friends, who then worked quickly to support Lilesa, sending officials from the foreign ministry to take him to the airport and begin his temporary visa application to stay in Brazil. Fearing he would be sought by Ethiopian authorities, Lilesa had left the Olympic Village immediately. Alone in his hotel, he was terrified when the Brazilian officials knocked on his door.

But when the Brazilian officials entered the room, they greeted him with smiles instead of the violence or the detainment he’d feared — and took him for coffee. On the car ride to the airport, he called friends in the US to inform them he was safe. By the time he made it to the US embassy after securing his temporary Brazilian visa, Lilesa was surprised by his newfound celebrity among Brazilians and how excited people were to see his medal.

But when the Brazilian officials entered the room, they greeted him with smiles instead of the violence or the detainment he’d feared — and took him for coffee. On the car ride to the airport, he called friends in the US to inform them he was safe. By the time he made it to the US embassy after securing his temporary Brazilian visa, Lilesa was surprised by his newfound celebrity among Brazilians and how excited people were to see his medal.

Fearing he would be sought by Ethiopian authorities, Lilesa had left the Olympic Village immediately.

“People were fascinated and they wanted to touch it and they wanted to look at it,” he said. “There was a moment when everybody stopped working and they were just lining up to look at the medal and that sort of made me realize that this is a big deal.”

Gemechu saw the warm reception firsthand when he walked around Rio with Lilesa: “Most of the time we were outside around the beach, and a lot of people there, they watched [him] on the TV and media, so we had fun. They said ‘Oromo!’” he recalled while raising his hands above his head to replicate the now-famous gesture. Stopping to high-five Lilesa periodically on the street, they heralded him as a champion of resistance whose symbolic act spoke to communities well beyond his own people. This support didn’t make up for being away from his wife and two young children, but it helped sustain him for the long, lonely journey ahead.

Lilesa at a press conference in Washington, DC, on Sept. 13, 2016. T.J. Kirkpatrick for BuzzFeed News

A conference at Washington, DC’s Phoenix Park Hotel on September 13 was an opportunity for Lilesa to keep attention on the issue he’d brought to the world stage at Rio and his second big hurdle after arriving in the United States. Earlier in the day he had held his first news conference outside the US Capitol, where he implored Congress members to intervene on behalf of the Ethiopian people. Congressman Chris Smith later announced the introduction of House Resolution 861, “Supporting respect for human rights and encouraging inclusive governance in Ethiopia.”

Stepping up to the podium, Lilesa immediately thanked the journalists in the DC hotel’s conference room, noting that freedom of speech is not a right he takes lightly. The urgency of the protests had been suppressed by state-run Ethiopian media and largely ignored by the West — until, of course, Lilesa.

“We Oromo have not had access to you in the media,” he told journalists through an interpreter, OPride.com founder and editor Mohammed Ademo. “We have been cut off from you. We have not had a free press in our country.”

Ethiopia has come under fire for restricting journalists’ freedoms in recent years. Ahead of the May 2015 elections, government forces had tamped down on dissidents, most notably charging nine bloggers and journalists with terrorism and arresting eight of them under the guise of the 2009 anti-terrorism law (one member residing in the US was charged in absentia).

Lilesa’s first language, like many other Oromo people, is Afaan Oromo. He speaks Amharic in a soft, self-conscious cadence. Lilesa is at his most vibrant when he speaks in Afaan Oromo, especially with the runners who approached him after the press conference. They came to him with beaming smiles, ushering him into hugs to thank him for his gesture. He was visibly relieved to be alongside people who are almost family. Among them was Demssew Tsega, a marathoner who has been in the US for seven months now. Tsega also testified at the news conference announcing House Resolution 861 on Capitol Hill.

One day last December, Tsega wound up amid a crowd of peaceful protesters on his way home from training for the marathon in Sululta, a city 20 miles north of Addis Ababa. Along with four other athletes, Tsega joined the protest. When government security forces came to apprehend protesters, three runners got away — but Tsega and another teammate didn’t.

“Because I’m a runner and the security forces recognized me since they’d seen me on TV before, they were especially keen on capturing me,” he told me in Amharic in October. “They jailed me for two days and tortured me on my feet so I couldn’t run anymore.”

Lilesa with runners Ketema Amensisa and Demssew Tsega, advocate Obang Metho, and runner Bilisuma Shugi Courtesy of Andrea Barron

Upon his release, Tsega did not seek treatment for his injuries at the local hospital because it’s run by the government.

“I was afraid they would arrest me again if I went to the hospital,” he said. “Before I lived with my family in Addis Ababa, but after [my arrest and torture] I hid in the countryside.”

When the notice that Tsega had met the minimum qualification to compete in the marathon arrived, he was conflicted. With injured feet, he had no hope of racing, and it seemed all his training had been for nothing. But he took the opportunity to secure a visa and came to the United States, knowing it was his only shot at accessing treatment for his injuries and one day racing again.

“They’re still looking for me now,” he said. “[The government] still harasses my father; they took our land.”

“I was afraid they would arrest me again if I went to the hospital,” he said. “Before I lived with my family in Addis Ababa, but after [my arrest and torture] I hid in the countryside.”

When the notice that Tsega had met the minimum qualification to compete in the marathon arrived, he was conflicted. With injured feet, he had no hope of racing, and it seemed all his training had been for nothing. But he took the opportunity to secure a visa and came to the United States, knowing it was his only shot at accessing treatment for his injuries and one day racing again.

“They’re still looking for me now,” he said. “[The government] still harasses my father; they took our land.”

Sitting next to Tsega at a downtown Silver Spring restaurant, fellow long distance runner Ketema Amensisa sighs. Before the government took 75% of their land, Amensisa’s family had 20 cows in Gebre Guracha, a central Ethiopian town in the North Shewa region of Oromia. Stripped of their primary means of income, the family of subsistence farmers has been struggling to survive since.

“We miss our country,” Amensisa said. “When we don’t have any other options as a people, we stand beside the government because we fear for our safety if we say otherwise.”

“We miss our country,” Amensisa said. “When we don’t have any other options as a people, we stand beside the government because we fear for our safety if we say otherwise.”

The two runners paused their stories intermittently to check in on Momina Aman, a teammate who arrived later in our conversation. Tsega mentioned repeatedly that he wants to take her to TASSC, the Torture Abolition and Survivors Support Coalition, the organization that’s been helping him access medical care for his foot, immigration support, and psychological care.

“I came to this country because Ethiopia’s government killed my father, stepmother, my sisters, and my brothers.”

“I came to this country because Ethiopia’s government killed my father, stepmother, my sisters, and my brothers,” Aman said through tears. “The rest of my brothers and I were only spared because we were in Addis Ababa.”

“We were in Addis Ababa when we got the call that our family had been killed,” she continued. “Recently another one of my brothers was beaten and left to die by government security forces.”

Aman’s brother was one of the 2 million attendees of this year’s Irreecha celebration the first weekend of October. Irreecha, the annual thanksgiving holiday that marks the shift from Ethiopia’s rainy season to the warmth and bounty of the dry months at the end of September, draws crowds of up to 4 million from across Ethiopia to the town of Bishoftu, about 25 miles southeast of Addis Ababa, to pray and sing alongside the crater lake Hora Arsadi. The festivities are filled with color and calm, an opportunity to reflect on the changing seasons and their attendant harvests.

“We were in Addis Ababa when we got the call that our family had been killed,” she continued. “Recently another one of my brothers was beaten and left to die by government security forces.”

Aman’s brother was one of the 2 million attendees of this year’s Irreecha celebration the first weekend of October. Irreecha, the annual thanksgiving holiday that marks the shift from Ethiopia’s rainy season to the warmth and bounty of the dry months at the end of September, draws crowds of up to 4 million from across Ethiopia to the town of Bishoftu, about 25 miles southeast of Addis Ababa, to pray and sing alongside the crater lake Hora Arsadi. The festivities are filled with color and calm, an opportunity to reflect on the changing seasons and their attendant harvests.

But this year’s Irreecha took place against the backdrop of heightened police presence in Oromia. State forces encircled festivalgoers, eventually firing a mixture of tear gas and bullets into the crowd after attendees began reciting chants associated with the #OromoProtests movement that has grown in the region in the last year. Some reportsestimate up to 678 people were killed between authorities’ violence and the resultant stampede.

When reports first emerged that the festival had turned violent, Aman stayed up all night trying to call her brother. She reached him in the morning, relieved to hear he was shaken but safe.

The festival’s deadly turn was covered widely in international press, despite the Ethiopian government’s control of state-run media in the country. Questions about Ethiopia’s future as beacon of the once-promising “Africa rising” narrative surfaced again in the West, pointing not only to the massacre but also to the simple gesture that put enough attention on Ethiopia for its people’s suffering to even matter outside the continent.

Immediately after the bloodshed at Irreecha, the government declared a three-day period of mourning. One week later, it announced a six-month “state of emergency,” under which the army was deployed nationwide and access to social media and mobile internet indefinitely suspended. In three weeks, over 2,000 people were detained for participating in anti-government protests, which government officials blamed on “foreign anti-peace forces” from neighboring Eritrea and Egypt.

“They laid their actions bare,” Lilesa said of the state of emergency. “But there’s nothing new here.”

A celebration of Irreecha held in Maryland the morning after the bloodshed in Ethiopia. Hannah Giorgis / BuzzFeed News

Even amid the uncertainty of the government’s state of emergency, Lilesa remains a beacon of hope for runners like Tsega, Amensisa, and Aman — and for Oromo people around the world.

In the time between Lilesa’s protest and his arrival in the US, two more Ethiopian runners had repeated the gesture as they crossed finish lines around the world. On August 29, Ebisa Ejigu won the Quebec City Marathon and followed in Lilesa’s footsteps. On September 11 — Ethiopian New Year — Tamiru Demisse did the same as he claimed the silver medal in the men’s 1,500-meter T-13 race at the Paralympics in Rio.

Even those who have not protested themselves see Lilesa’s actions as a path forward, an opportunity to rally around one another especially as Ethiopia’s government continues its crackdown. It’s an act they see as fundamentally patriotic: If he didn’t love his country, he wouldn’t want it to be better.

For Tsega, Lilesa’s action and the ensuing media attention was a matter of life and death: “I know sports and politics don’t always go together, but when situations are this urgent, it’s something you have to do even if it kills you. Leaving his children, wife, and all his possessions behind, he… I don’t even have the words. He did all that for his country, for his people.”

“I know it was hard to say that,” Amensisa added. “But after Feyisa did it, he opened up a new path for us.”

“I know it was hard to say that,” Amensisa added. “But after Feyisa did it, he opened up a new path for us.”

All of them are hopeful for the potential of Lilesa’s spotlight on the issue to attract more international intervention in the area — especially from the US, long a military ally of Ethiopia. In the weekend following his arrival in the US alone, there were over 60 news stories on Lilesa and the Oromo protests.

Many of them called for the US government to halt aid to Ethiopia until the totalitarian nature of security measures in the country are addressed. Some of the sanctions being sought by the community are reflected in Congressman Smith’s House Resolution 861 and the identical 21-cosponsor Senate resolution introduced in April.

Many of them called for the US government to halt aid to Ethiopia until the totalitarian nature of security measures in the country are addressed. Some of the sanctions being sought by the community are reflected in Congressman Smith’s House Resolution 861 and the identical 21-cosponsor Senate resolution introduced in April.

But Lilesa’s impact reverberates far beyond runners’ circles, community events, and the dense Ethiopian population of the DC metro area. As conversations about athletes’ political voices continue to gain steam following Kaepernick’s silent protest of the American national anthem, Lilesa remains a lightning rod for a community divided by both politics and geography.

On Twitter, the hashtag bearing his name is most often used to share updates on news regarding the community at large. Facebook and Viber — when not being axed by the government — remain digital organizing hubs. And on Snapchat, a massively popular channel for Ethiopian and Eritrean youth held a discussion about Oromo politics earlier this month while one of its hosts wore a shirt printed with Lilesa’s name and face.

“BunaTime” (taken from the Amharic word for coffee) draws an average of 15,000 views per Snapchat story, and Ethiopian and Eritrean youth from around the diaspora take turns hosting it for several hours at a time. Its attendant Twitter and Instagram channels boast almost 10,000 and 37,000 followers respectively.

The Oromo-led Snapchat teach-in drew both excitement and ire from young viewers. But hosts were clear: Lilesa, and the #OromoProtests, are the future — not just for the Oromo community, but for all of Ethiopia.

And Lilesa is committed to keeping his career going, despite the complications. He has been training in Arizona since last month. The choice to head west was made partly because of the state’s altitude, and partly, Gemechu joked, because “he don’t like snow.” Lilesa had briefly considered Kenya as another training location, but fears that the Kenyan government’s close relationship with Ethiopia’s would lead to his extradition kept him from pursuing that option. He would’ve been closer to his family, but recent developments in Ethiopia reinforce his decision to stay away from the region.

“The crisis puts [runners] in a position where we can’t focus on our training,” he said. “If this continues without any change, Ethiopia may not win as many medals as it used to.”

Lilesa won’t be running in the New York City Marathon in November, but he has plans to run in both December’s Honololu Marathon and next April’s race in London. The return to the sport he loves has left him energized, but tensions flaring up back home — and his own distance — continue to sap him of energy.

Lilesa won’t be running in the New York City Marathon in November, but he has plans to run in both December’s Honololu Marathon and next April’s race in London. The return to the sport he loves has left him energized, but tensions flaring up back home — and his own distance — continue to sap him of energy.

“I left my country and I live in a strange country,” he said when we spoke recently. “How could I feel the same comfort I did before? How could I feel happiness?”

Lilesa photographed on September 13, 2016. T.J. Kirkpatrick for BuzzFeed News

Both his own future and that of his country feel tenuous at the moment, a heavy sense of both revolutionary excitement and dread hanging over both. Lilesa speaks to his wife and children regularly, but hasn’t seen any of them since August 17. “I don’t feel weight on myself since I did what I did, because I believed in it,” he said. “But I do worry about my family back home.”

He was careful and exacting when speaking of his 5-year-old daughter and 3-year-old son in hushed tones: “I don’t want to look at my children any differently from others in my country who are being killed,” Lilesa said. “They face the same fate and the same destiny like all other children in Ethiopia.”

He knows he cannot return to them until the political situation changes, but hopes now that he will one day be able to see them in the US if it doesn’t. The decision to live here for now — even and especially in exile — weighs on him, a sense of guilt pervading his words as he responds to the fact that Oromos around the world now consider him a hero.

“The one who leaves isn’t a hero,” he said recently. “Heroes are the ones who go and fight alongside the people.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)